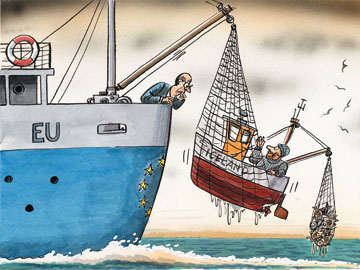

Iceland hopes to start accession talks with the European Union by July, although the island’s government and its 320,000 people remain deeply divided over whether to join the bloc.

Prime minister Johanna Sigurdardottir, leader of the Social Democrats, announced late on Sunday that she had finally reached a compromise on EU accession with the Left-Greens, who oppose membership, that would enable the two leftwing parties to form a new coalition after their election victory two weeks ago.

The Social Democrats are the only Icelandic party that strongly backs EU membership, while most Left-Green deputies oppose even opening talks with the EU.

Popular support for accession has risen following the island’s financial crisis last autumn, with many voters hoping that adoption of the euro would prevent future economic turbulence. Last year the Icelandic krona lost 85 per cent of its value against the euro, pushing up inflation and increasing the burden of foreign currency-denominated mortgages.

As a compromise, the coalition will put a bill before parliament next week seeking authority to open talks with the EU but deputies will be given a free vote. The terms of the accession treaty will then be put to a referendum.

The Social Democrats believe they will be able to win enough votes from the opposition Progressive party to secure the bill’s passage, though they may be forced to consult regularly with the opposition on the progress of the talks.

“There is a parliamentary majority for EU membership talks,” Ms Sigurdardottir told a news conference.

Opinion polls show that currently 60 per cent of voters would support membership, but this could easily disappear if the island were to make big concessions on fishing rights in its accession talks.

Eight of the 10 cabinet ministers are continuing from the leftwing caretaker administration that took over in February after the Independence party-led government was forced to resign over the island’s financial crisis.

The new government’s immediate challenge will be to stabilise the economy by reducing the budget deficit – which it plans to return to balance by 2013 – restructuring the banking system and completing talks with creditors over the banks’ $80bn in foreign debt.

This should enable Iceland to get back on track with the $10bn stabilisation plan agreed with the International Monetary Fund. The IMF halted further aid following the collapse of the Independence party-led government.

RELATED ARTICLES

- People in Iceland experience COVID-19 reinfection despite massive vaccination rates

- Iceland Declares the COVID-19 Pandemic has Ended, All Restrictions Lifted

- Denmark and Norway close borders for everyone but 'asylum seekers'

- Volcano Erupts in Iceland, Lava Reaches town of Grindavik

- Iceland evacuates residents of Grindavik following Volcano-induced Seismic Activity